Sarah Davidson

BIOMASS: I'm so glad that we are having this conversation today. Are you currently in your studio?

SARAH DAVIDSON: Yes, I'm in my studio in Brooklyn. Well, technically it's in Ridgewood, Queens, but right on the border. I’m looking out at beautiful gray New York.

BIOMASS: I would love to dig into your recent exhibition Fingery Eyes. Could you describe your drawings and paintings for those less familiar with your work?

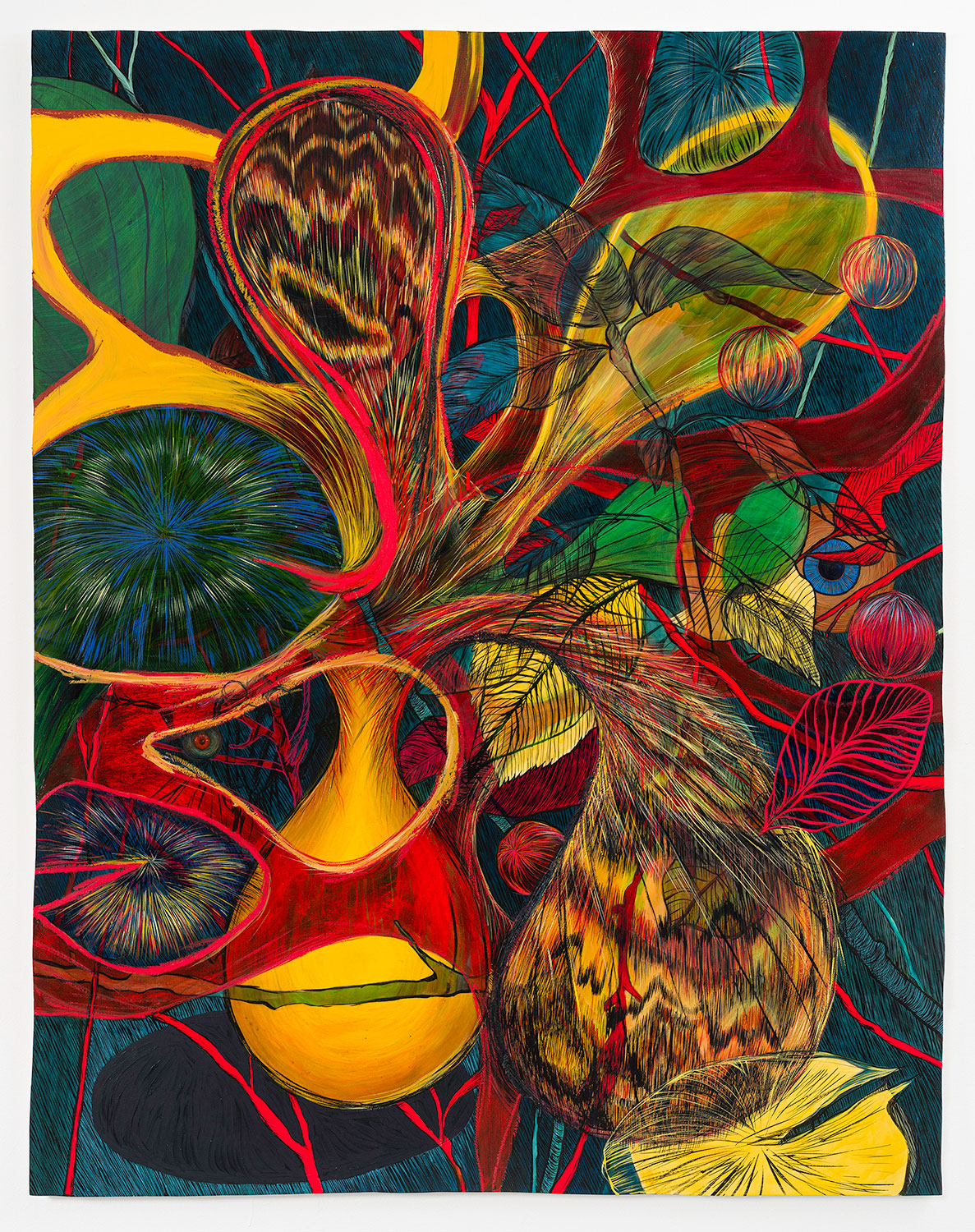

DAVIDSON: In terms of what they look like, I would describe them as a combination of biomorphic abstraction, and recognizable things borrowed from a tradition of natural history illustration. There's a recognizable drawing style that I think, even if you don't know the specific people I'm pointing to, reads as the type of illustrations you would see in a field guide, and has lots of saturated color. I've recently been obsessed with eyeballs, because I've been thinking a lot about observation. So I thought, at some point a few years ago, it would be productively uncanny if the work suggested that it was looking back by having eyes in it. So all the work in Fingery Eyes had eyeballs somewhere in the composition. They're generally non-human eyes, they're almost all frog eyeballs, some are stylized human eyeballs, and some of them are just abstract, spherical forms that maybe could be eyes. I also riff, compositionally, on the idea of an eyeball. There is also a back and forth between abstraction and figuration, and it’s unclear if what you're looking at exists on a human scale, or if it's microscopic, or if it's an insect. I like that sort of ambiguity.

BIOMASS: Yeah, I really enjoy how the work kind of confronts you with these eyeballs and how you play with micro scales in your paintings. When I am looking at these works, sometimes the work has these enmeshed, organic layers that open up into holes. And sometimes those holes are filled with unexpected details or phenomena. And it has a similar experience to when you're in a wilderness thicket, or when you're looking closely at organic or natural phenomena and discovering the details of something in that way. When the eyeballs appear however, there's a forced self-awareness that kicks in, a flip occurs and the work looks back. How would you describe that process of creating this visual language? And in particular, how did you develop your sketches and field notes?

DAVIDSON: The work has evolved over time. I worked as a nature guide, in very remote parts of the wilderness all over North America and Scandinavia for 10 years. That was the initial place where this work started evolving, because I would draw from observation during these work trips. I didn't necessarily think of it as my art practice, but I have all these notebooks with observational drawings. Alongside that, I would just arbitrarily draw shapes, these little biomorphic blobs, and then fill them in with observations of what I was looking at. This usually happened while I was sitting on the ground, waiting for people to get ready. So, it's the kind of stuff that you find on the ground, not landscape drawings, things like pine cones, bits of foliage. Things that are recognizable sometimes, also textures. At this same time, I was teaching species ID and environmental studies, thinking about the history of the idea of wilderness. The more you learn – depending on your code of ethics – about the history of the idea of wilderness in North America, or the history of the idea of ‘nature’, like the separation between humans and other-than-human forms, and the kind of ideologies that have shaped wilderness in North America, the more you feel conflicted. For instance, North American ‘wilderness’ is often contingent on there not being indigenous people present, which is of course, not true. The idea of ‘nature’ is also often defined in opposition to what is considered ‘unnatural’, which means this concept of nature has often been used to exclude queer people and non-white people.

As I was learning more, I was also looking at these beautiful illustrated field guides in order to teach people about natural history. So, there is a lot of ambivalence there for me, because I'm really drawn to those illustrative languages visually, but also I understand them as being wrapped up in this complicated, and often harmful way of separating ourselves from the world. So for me, the mode I'm working in is a way of using some of that visual language to create these more immersive worlds. Where you're enmeshed as a viewer, and the bodies that are suggested in the works (human and non-human) are interacting in ways that are intentionally confusing. For me, that's more accurate and more interesting. It is a reflection of my ambivalence. I'm drawn to those visuals, but I can't just recreate them, I have to put them in a more complicated context.

BIOMASS: Yes, I really appreciate the acknowledgement of those flattened histories through early scientific illustrations or like, colonial bioprospecting and how that frames our perspectives on shared ecosystems. I'm curious if you are referencing some of these violent histories, is that where the dripping blood comes from?

DAVIDSON: You mean the blood drops in the paintings? No, I hadn't really thought of it that way. I mean, I'm not opposed to that reading at all. Honestly, I was thinking of them more in the sense that, I've been including bodily elements like the eyeballs because I'm curious about body horror, or cartoony ways of treating the body, which are all body horror because you're abstracting parts of the body, like an eye popping out or a tongue. I use some of the strategies that cartoons do, because I don't want the work to be totally grotesque, but I do want it to be uncanny. Basically, I want people to get into looking at it before they realize what they're looking at, which might be a blood drop or a disembodied eye filled with insects. So the blood drops, I wasn't thinking of in a historical way, I was interested in how creepy it is and how true it is, to be crossing boundaries like skin.

BIOMASS: Yeah, there are multiple access points for interpretation. I mean, from a distance the work has these magnetic, high chroma, vivid images. At the same time, complicating that relationship for the viewer is an interesting trick or disorientation of scale. I think it allows for, yeah, multiple different readings and new understandings of the subject matter.

DAVIDSON: There's also this through-line of butterflies and moths, which I’ve included for the last few years in the work. Partly because they often have these deceptive eye patterns on their wings, which was interesting to me. There is also a personal angle; one of the major questions that's at stake in the work for me right now is thinking through my own experiences as a trans non-binary person, and transitioning during the pandemic. Part of the work is just expressing that experience, and there may be an overly obvious metaphor, in these beautiful bugs that transform. But also, the kind of conceptual question there is: how do you articulate a queer or trans perspective in work that doesn't really depict humans? Metaphorically or literally, there are animals that are arguably queer or trans in different ways. But I’m also thinking about it abstractly, in this painting vocabulary that's really emphasizing transformation and the porousness of boundaries between different forms and different bodies. So that's in there as well, but it's a working question.

BIOMASS: That is a beautiful working question. I want to talk about transformation as well. Many people say that the realities of creative labor are so challenging, “why choose this path with all these obstacles?” kind of thing, and for trans folks among other marginalized people, these instabilities, financial and political realities are often compounded by harmful policies, poor leadership, or lack of support. But still, a creative life is a way forward amidst these barriers. Do you think artistic practice supports transformation? Or is that too big or too personal to handle through art alone?

DAVIDSON: It's complicated. I mean, I have a lot of conflicting feelings and thoughts about that. On one hand, it's very vulnerable to talk about yourself, especially in art, when it feels like sometimes it's a bit of a cop out to talk about your identity. And also, sometimes it just feels too vulnerable to share things about yourself. But also, as an artist, I'd be lying if I said my lived experience isn't what motivates the work. Obviously, this is me and my life experience shaping what I'm interested in as an artist, on a level that's not even conscious. I make work that's me thinking through my own experience of the world. So it's, of course, going to be in there.

And also, when I say it's a working question, for me of thinking through queerness, and transness in relation to painting and drawing, I mean that that question involves doubt. There's an ongoing field of queer ecological thinking that I'm influenced and inspired by, but at the same time, I'm not always convinced that making a painting is actually reflecting that thinking. So it's kind of like a maelstrom of these conflicting things. Also, yeah, of course, there are systemic barriers to people thriving, especially if you're not living in a normative body or living in a white body. And I have a lot of privileges as a white person in the world. So, it's complicated. And yeah, of course, as self-employed artists, we don't have paid medical leave to medically transition. Art feels like a realm in which you can talk about complicated, embodied experiences in ways that are complicated and conflicting and don't have to be literal. I mean, if I could express my ideas just in words, I wouldn't be a painter. I really like getting into some of those complications, I think that's actually where real transformation occurs. And I think that the work really embodies that. Nobody wants to talk about the spiritual side of their practice, but for me, I don't think it would be creatively fulfilling if there wasn't a spiritual motivation to make art. It fulfills needs that don't have anything to do with capitalism. It's just a thing that I have to do.

Studio detail. Courtesy of the artist.

Studio detail. Courtesy of the artist. Exhibition view of Fingery Eyes. NARS Foundation, 2023.

Exhibition view of Fingery Eyes. NARS Foundation, 2023.BIOMASS: Over the years, what relational practices have you found to be supportive, sustainable for you to continue to make your work? I ask because it is very common for artists and creatives to experience burnout, overwhelm or social anxieties. And I think it's useful to share practices and tools, even if they're individualized. What has allowed you to maintain your practice? And what people or communities have filled your cup as an artist?

DAVIDSON: To some degree, doing things that don't have to do with art is very helpful. I spend a lot of time in so-called ‘nature’, like, I go hiking a lot! I require that in my life, some space to not be immersed in the so-called ‘professional’ side of art making. I like to check out from that world regularly. Also the older I get, the more I'm able to separate those worlds, whether I'm selling work or whether the art has value in and of itself. I have to be conscious not to equate those two things, which is really helpful. Obviously, we live under capitalism, it's hard not to get wrapped up in that, we have to fulfill our basic survival needs. It's not like I don't need to make money in general, but I have never been able to rely on my art practice as my main source of income. So, I think just being really clear eyed about that. The amount of money that I make does not reflect how good the paintings or drawings or artworks are. And frankly, in terms of connecting with other artists, I don't really feel a lot of pressure to make sure my friends are the most famous artists or whatever. I build friendships with people who I feel a real kinship with, or whose values align with mine. I also have friends who aren't artists. I don't really approach networking as like, “oh, I have to become friends with a certain person”. I build long term relationships with people as friends or as ‘professional contacts’, just based on a connection, then it doesn't feel so fraught. I mean, it's complicated, because the boundaries are so blurry in the art world between what you do for fun and what you do for work; when you're just hanging out, and when you're making contacts. It can be very hard to navigate.

BIOMASS: Mmhm. You had mentioned that, looking at the work as valuable, just by being with that experience of seeing one’s ideas coming into fruition. That is such an intangible thing to describe or to convey, or to teach. And yet, it seems to be one of your biggest kind of resiliency tools.

DAVIDSON: Yeah, I think so. I mean, I'm sure you've experienced this, too, where you have a show, and you work towards it for months or years, and then the actual experience of the show can be so anticlimactic. If anything, I usually get a kind-of postpartum depression once the show has opened, or when the work is finished. I'm not saying that I have figured this out, because I still get depressed when I have a show. But, I feel like the only way to work through that is to place the emphasis on finding or creating meaning in the part where you're making the work and not the part where you're showing it.The practice has to be where the meaning is or else it can feel like a really emotionally impossible situation: always working towards this thing that weirdly disappoints. I feel like most artists get that depression, and it feels ungrateful or something, because obviously you want shows to work towards, and it's something to be excited about and proud of. But, if my sense of purpose as an artist only comes from shows, and each time they happen I get depressed and worried about what's next, that is not sustainable.

BIOMASS: You're articulating in that entanglement. By returning to your practice that allows for continuity and a reference for stability. And, yes, it's so easy–even celebrated and encouraged–to hang all of one's hopes, dreams and expectations, even financial needs, on external validation, through shows, sales, accolades, reviews, blah blah blah. Yet the reality for so many working artists, does not feel or look like that at all. The majority of the art world is in our practice.

DAVIDSON: It’s 100% capitalism! You could get a show that you would have been so excited about five years ago. Your mind would have been blown that you'd gotten this opportunity at this particular space. And now that you have it, you're like, well, now what? What's the next step? There is always more to want. It's the same as the ‘lifestyle creep’ that happens, if you start making a little bit more money, suddenly you want nicer things. It's an unending situation. It's okay to have ambitions, I have ambitions, but it can also be a really toxic way of thinking, especially about art.

Harry, oil on panel, 6 x 8.5, 2023

Harry, oil on panel, 6 x 8.5, 2023

Sarah Davidson (they/them, b.1989, Canada) works primarily between drawing and painting to create compositions in which shadowy, biomorphic figures and delicate, foliated fragments mingle. Making reference to a history of discourses constructing the ‘natural’ world, their works investigate bodies, environment, observation, and the tangled strings which often bind them together. While often drawn directly from ‘nature’, their drawings diffract distinctions between embodied self and other through a queer ecological lens: critters and space collapse into one another, suggesting a permeable web. Both the eye and the mind work towards the known--animals, plants, brush marks, lines--but are caught in a space of undoing. A question floats among the forms: who’s seeing who, and how?

Davidson lives and works in New York, NY. They have exhibited their work widely in Canada and the United States, including solo exhibitions at NARS Foundation, Brooklyn (2023), Wil Aballe Art Projects, Vancouver (2022), Feuilleton, Los Angeles (2021), and Erin Stump Projects, Toronto (2019). Their work has been covered by press including ARTnews, Canadian Art, Mousse Magazine, and Art Viewer. They have taken part in residencies at the Banff Centre, Banff (2020 and 2022), NARS Foundation, Brooklyn (2022) and AiR Sandnes, Norway (2017). Their work is included in the collections of the Royal Bank of Canada and the Burnaby Art Gallery. They received an MFA from the University of Guelph in 2019, and a BFA from Emily Carr University of Art & Design in 2015.