Sol Hashemi

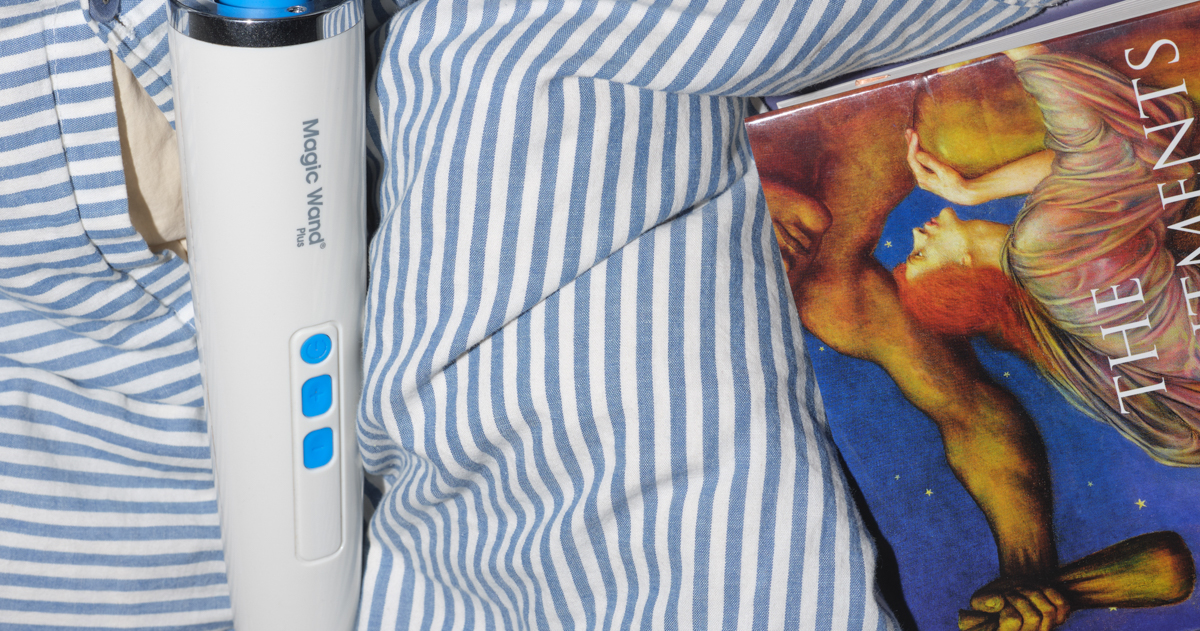

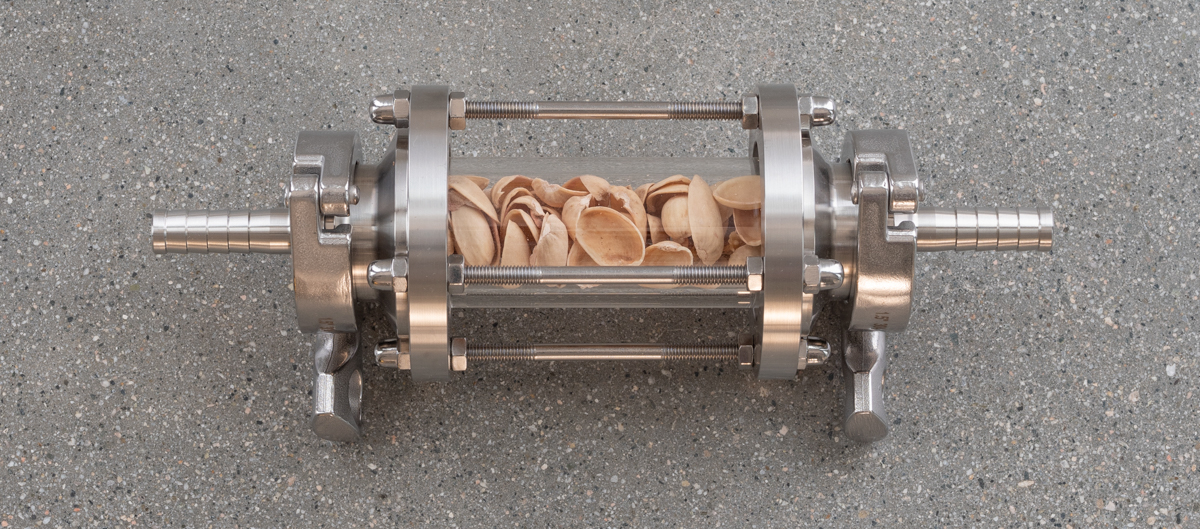

Sol Hashemi, Detail of Baker's Dozen, 2021, materials variable, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gaia. Photo: Sol Hashemi

Sol Hashemi, Details of Baker's Dozen, 2021, materials variable, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gaia. Photo: Sol Hashemi

Sol Hashemi, Details of Baker's Dozen, 2021, materials variable, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gaia. Photo: Sol Hashemi

Sol Hashemi, Details of Baker's Dozen, 2021, materials variable, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gaia. Photo: Sol Hashemi

Sol Hashemi, Details of Baker's Dozen, 2021, materials variable, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gaia.

Sol Hashemi, Details of Baker's Dozen, 2021, materials variable, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gaia.

BIOMASS: Hi! So happy to have you here to talk about Baker’s Dozen, but I also wanted to ask more broadly about your work and practice - what are some consistent questions your practice is devoted to?

Sol Hashemi: Yeah, I guess going back, my BFA was in photography and also as a child was very interested in photography, specifically nature photography. That was my initial focus, then being exposed to contemporary art I started to shift my understanding of what nature photography could be. And now I feel that I’ve come full circle to reconsidering what photography is at this moment and looking at processes as opposed to a static notion of nature, separate from humans. I also have had an interest in objects and their agency for a long time as well. Now, I’ve been approaching the work by reconsidering my interest in object agency, by considering the genesis of the object. So through the exhibition Baker’s Dozen, I made a photo book but the prints are on cans of beer instead of enclosed in a book.

B: What are the specific material components that make up the project Baker’s Dozen?

S.H: The project, uhm, it’s very hard to define where it starts and where it stops, so I’ll describe the process first. I’ve been brewing for the past year, kindof using more standard brewing ingredients like hops, barley, yeast, water, but then also modifying some of the processes or finding local materials, local plants and learning about the history of brewing and plants previously used for bittering. And also plants, such as juniper, used for cleaning water or vessels. Using plants like cedar and western hemlock. I’m also working with yeast, water and grain, and the process of brewing. It’s actually very similar to working in a dark room, working with temperatures, chemistry and exposure. My approach is to modify and collaborate with the materials, not just a set recipe. So the work is all those things, and then I produced custom shrink sleeves for the cans, and thirteen images which were made mostly over the last year, and show or involve processes of foraging, baking, by myself and with others such as Rosamunde Bordo… the images cover a pretty wide range of situations that arise out of taking part in these processes and ways of living. The photographs document these situations, but then also become something where they work across sight and show a document of me learning these processes. They also sit beside the beverage - in cross-modal correspondence, altering the beverage itself, or peoples experience of it. I want to show how the image can be functional, embedded and part of a new image formed.

B: And how did you think through displaying works that are process based?

S.H: In this installation there is a row of bays and a shelf in each bay and a fridge where beer was stashed inside. As well as some empty cans, labels, and showing the process in the installation. I wanted to create something and break down the black box of its creation and lead the viewer through the process that becomes a can of beer.

B: In a way it seems like you're attempting to create a holistic project or maybe product? Can we talk about beer for a second? It has this interesting history and I’m curious, what stood out to you in your year of fermenting?

S.H: One thing is thinking about yeast as living. The symbiotic relationship between yeast and humans became interesting to me. Also the history of beer as being something that is a water preservation method. To eliminate the need for modern water systems. Beer solved a lot of problems through alcohol, that now chlorine is used for or various chemicals. Beer was traditionally made with a much lower percentage of alcohol, called a “small beer” with around 1 or 2% APB and many people around the world have made other types of beverages to preserve water. So many had it as a form of drinking water. The history of small beer is interesting to me. And also the culture around sites for drinking was cool to learn more about like saloons umm there is one book that mentioned in particular *gets up to grab book* in a book by Lars Garshol, Historical Brewing Techniques the lost art of farmhouse brewing. Where he talks about the trick cup, which is a cup that requires a few people to solve a puzzle together and not spill the beer in order to drink it. This societal and communal relation was interesting, also looking at the history of prohibition as a form of class war, rather than the beer, or drinking, being what was predominantly affected by prohibition, it was working class communities that were stationed around beer production and consumption. These really important spaces were targeted in prohibition through the closing of the saloon and other communal spaces. I think that’s an important aspect of the research.

Sol Hashemi, Detail of Baker's Dozen, 2021, materials variable, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gaia.

B: These ideas connect to this past year as well and the loss of close-knit space to a certain extent. Since your work is informed by different bodies of research, in your own experience at what point do you know something is crystalized?

S.H: I really resist the artwork becoming something static, when it becomes static it feels dead to me. So I try to consider the artworks as living, and look towards ways that I can allow that. Options for displaying past and future works, modifying a linear timeline to have potential beyond one installation. I think that is a tough question, because there is no set way they become artworks. I do think of them as photographic, I’m working with all these processes from various niches but I’m trying to be open to the materials and work with their histories and communities and allow for a new situation or artwork to emerge that I could not have reached on my own. I think when I can recognize something’s emergence as separate from something I had planned it becomes much more of an artwork to myself.

B: In a way it sounds like you locate your practice within a cycle of transition, as opposed to a single time and place. It involves not just the acknowledgement of transformation but the necessity for it. It almost sounds like your practice creates potential artworks. Would you say that is accurate?

S.H: Yeah I think that’s exactly it. I think of the practice or artwork as the phase between states.

B: What therefore would you say gets in the way of that flow, in your practice?

S.H: I think just not learning, or immersing myself in a mixture of fields. If I was to only approach a project from an art historical perspective or only technology, limitations within one field I think really restricts my thinking. The importance of learning and diving into various fields and to not just make art that's about bringing other fields into an art context but really trying to think in a different way. Gotta keep it unpredictable! If the practice becomes predictable for me, there’s no point in having a practice.

B: Sometimes institutions can be a source of burnout, at this point having completed your MFA program, how are you thinking of regenerating and refilling your creative resources?

S.H: Actually I think the brewing has been a factor in not burning out, even though it's a lot of work. I really enjoy cooking, I love cooking Persian dishes with a few ingredients and so… that has helped. For me it’s actually the opposite, I felt burnout before grad school and it helped me get out of that.

I recently spent some time on Salt Spring Island in Germaine Koh’s Hemlock Micro Studio. It’s been my first in-person residency and has been very generative. I harvested apples with Germaine and Rosamunde and used Germaine’s DIY apple press to make four small batches of apple cider while photographing along the way. One of the batches was canned outside during an atmospheric river!

And, I’m currently setting up a former restaurant as my art studio thanks to a pilot project that the Vancouver Mural Festival has organized. Having space to work across all the niches of my practice at once is something that I am very excited about. I’m in the Royal Centre Mall, and I’m looking forward to seeing what I can do with this public setting!

Sol Hashemi, Detail of Baker's Dozen, 2021, materials variable, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Gaia.

Sol Hashemi views his artworks as mushrooms popping up occasionally from a vast mycorrhizal web. His practice spans many niches, including foraging, woodworking, experimental product photography, stoneworking, cooking, organizing, conceptual floral design, writing, conversation, curating, brewing, and the internet. He has exhibited his work internationally, including the James Harris Gallery (Seattle), Annarumma Gallery (Naples), Sculpture Center (Long Island City, NY), Ditch Projects (Springfield, OR), Portland Art Museum, and Kunstverein München. Hashemi was a cofounder of the art space Veronica (Seattle) and is a recipient of the Kayla Skinner Award from the Seattle Art Museum. His publication, Excerpt of Baker’s Dozen, was recently published by Artspeak (Vancouver).