Steven Cottingham

Steven Cottingham

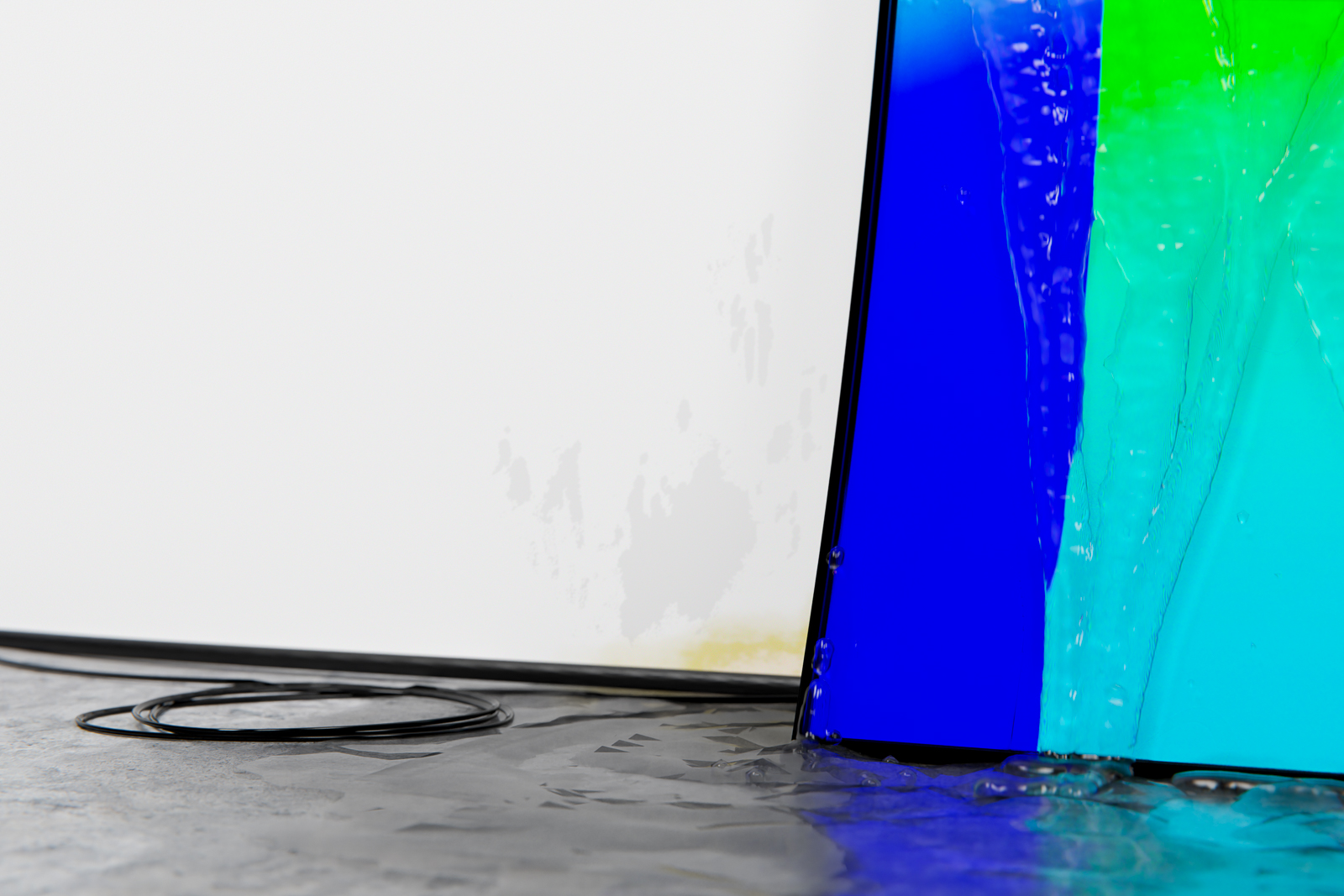

Liquid crystal display. 2020,

curved LCD screen, garden hose,

pump, hardware, water.

57 x 34 x 17 in. (145 x 86 x 43 cm)

Steven Cottingham

Drone flock boid sim. 2020.

Digital rendering and animation

with sound. 1 minute, 27 second.

Steven Cottingham

Liquid crystal display. 2020,

curved LCD screen, garden hose,

pump, hardware, water.

57 x 34 x 17 in. (145 x 86 x 43 cm)

Steven Cottingham

Liquid crystal display. 2020,

curved LCD screen, garden hose,

pump, hardware, water.

57 x 34 x 17 in. (145 x 86 x 43 cm)

Steven Cottingham.

Fluid simulation, 2020

BIOMASS: Could you talk about what you’ve come to like most about the rendering aspect of your practice?

Steven Cottingham: What I like the most is the level of control I have in making artworks. By that I don’t just mean making use of the computer's ability to do a high level of craft while working non-destructively, but also the level of control it offers economically in addition to aesthetically. There's no price barrier in terms of producing or fabricating works; the software is open source and the tutorials are free on youtube. So I can quickly visualize different works in gallery-looking spaces, and in this current artistic climate visualizing a work is basically the same thing as making it.

B: Because so many people are still learning the language of software, maybe you could describe what your process includes?

SC: When I say rendering I'm referring to a set of practices. The first one is modelling or sculpting: creating virtual objects out of digital geometries. And then there’s the process of shading where you give the geometry a surface or texture and you tell it to interact with light in a certain way. And then there is a process of compositing and animating and finally circulating the images that you make. As I become familiar with these processes, I’m finding a lot of analogies to other forms of artistic practice. I described sculpting but there is also a sense of painting—creating images out of nowhere—and then photographically composing the sculpture in digital space. But there’s also a sense of choreography and performance when working with animations and simulations, you are asking the computer to do things and it responds.

Steven Cottingham. Drone model, 2020

B: That’s an interesting way of thinking about it, would you say there is overlap with film or cinema?

SC: Yeah definitely. One media theorist, Lev Manovich, makes an argument that photoreal rendering in film is not a new phenomenon but actually belongs to a very old tradition where the images would be handmade, they’d be drawn or animated or planned rather than captured by cameras. The idea of capturing images is in many ways the newer discourse.

B: Hmm. Who else have you got up your sleeve? Theorists, philosophers, writers?

SC: I just read a really good essay by Linda Nochlin on realism, where she’s talking about how artists who have pursued realist subject matter throughout history have often been greeted with accusations of not being creative enough by drawing on what's in front of them. But ultimately they were representing things that wouldn’t have been depicted otherwise, like in the period of 19th century French realism where artists were depicting peasants and labourers which hadn’t really been portrayed in painting before—typically it was the other end of the social spectrum, opulent still-lives and portraits of aristocrats and stuff. So I really like how she describes the act of pursuing realism as one of upsetting how power has been represented and therefore how it operates on some levels.

B: So how have you arrived at some of your own subject matter if this is a point of consideration for you? And are those ideas visible in the BIOMASS exhibition work?

SC: Well I’m very excited about the BIOMASS project as a whole, happy to be contributing. Um so this work is going to be basically a sculpture that has a video component, it’s a television with water pouring over it. Right now I’m trying to get the water to behave in a watery way (laughter). The project as a whole is trying to find different ways of thinking about what’s real or what’s not real in terms of if images could be said to be real or their effects on reality. Of course images are always taking shortcuts as they translate one thing from one place and represent it in another, so it's a process of sort of interrogating those shortcuts or the decisions that are made around what to include and what to exclude in a depiction. In this sculpture I'm trying to include the screen itself which is often repressed: we don’t often look at them, we look through them into an illusionistic space, so I wanted to consider the reality of the screen itself by simulating water pouring over it.

B: Do you think this sculpture and installation would be possible IRL?

SC: The potential electrical hazard is definitely exciting to me, even though it is not a physical threat, I think it still sets off a certain kind of alarm bell for the viewer.

B: Knowing some of your previous work, what do you think you gravitate to in hazardous things?

SC: They’re just like, forbidden! (laughs) I enjoy making artworks that have a sense of danger in them because I feel it’s not only something you can feel with your body, like a kind of aversion to whatever that harmful substance would be, but it's also one that the capitalist economy itself recoils from on the basis of being counter-productive. It’s also then a way to think about the kinds of destruction and danger that are permitted, like pollution, waste, and exploitative working conditions.

B: Which resources do you find most precious in your own practice?

SC: Always it’s time.

Steven Cottingham is an artist based in Vancouver. His practice concerns the dialectic of profit (the production of more than is consumed) and friction (the consumption of more than is produced). In 2020, Cottingham had solo shows at the Alternator Centre of Contemporary Art (Kelowna) and Wil Aballe Art Projects (Vancouver). Since 2018, he runs QOQQOON, an art theory webzine.